That said, the inadequacy of traditional models for valuing cryptocurrencies does not imply the absence of value altogether. After all, tech-savvy individuals and, increasingly, sophisticated institutional investors abound in crypto markets, suggesting that there are compelling dynamics at work not captured by standard financial frameworks. The question, then, is this: If cryptocurrencies do not themselves generate measurable returns, where does their value come from?

The birth of Bitcoin

To understand why the value of cryptocurrencies has remained so contested, it helps to return to their origins. Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency, emerged from a 2008 White Paper published under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto at the height of the global financial crisis. For most, we will remember this as a period marked by systemic failure and collapsing trust in banks and governments in the West.

See also: Markets rise when merit is recognised

The core objective of Bitcoin was to offer a radical alternative to the status quo. Far from being designed as an investment asset, Bitcoin was born in the margins as an experiment in digital autonomy, drawing from the same ideological currents as anti-censorship and cyber-dissident movements such as the cyberpunk activism of 1980-1990s in the US.

Bitcoin’s design combined cryptography, distributed networks, game theory and engineered scarcity to create a monetary system capable of operating without trusted intermediaries. Over time, however, and as the crypto ecosystem developed, cryptocurrencies gradually evolved beyond their original ideological foundations.

This is hardly surprising. As we have written in the past, technologies often outgrow their initial purposes, accumulating new meanings, uses and market roles as adoption expands. Crucially, while much of crypto’s subsequent financialisation has focused on speculation and wealth creation, these developments are arguably secondary to its core breakthrough: decentralisation. Blockchain technology, built on distributed networks, forms the foundation of crypto’s trustless system and enables true decentralisation. Cryptocurrencies can be stored and transferred without the need for trusted intermediaries, thus enabling transactions that can bypass capital controls, political repression and banking exclusion. It is this property, more than its price appreciation, that underpins one of crypto’s most durable functions: as an exit asset.

See also: Base MHIT plan by Bank Negara Malaysia — a step in the right direction

A short history of exit assets

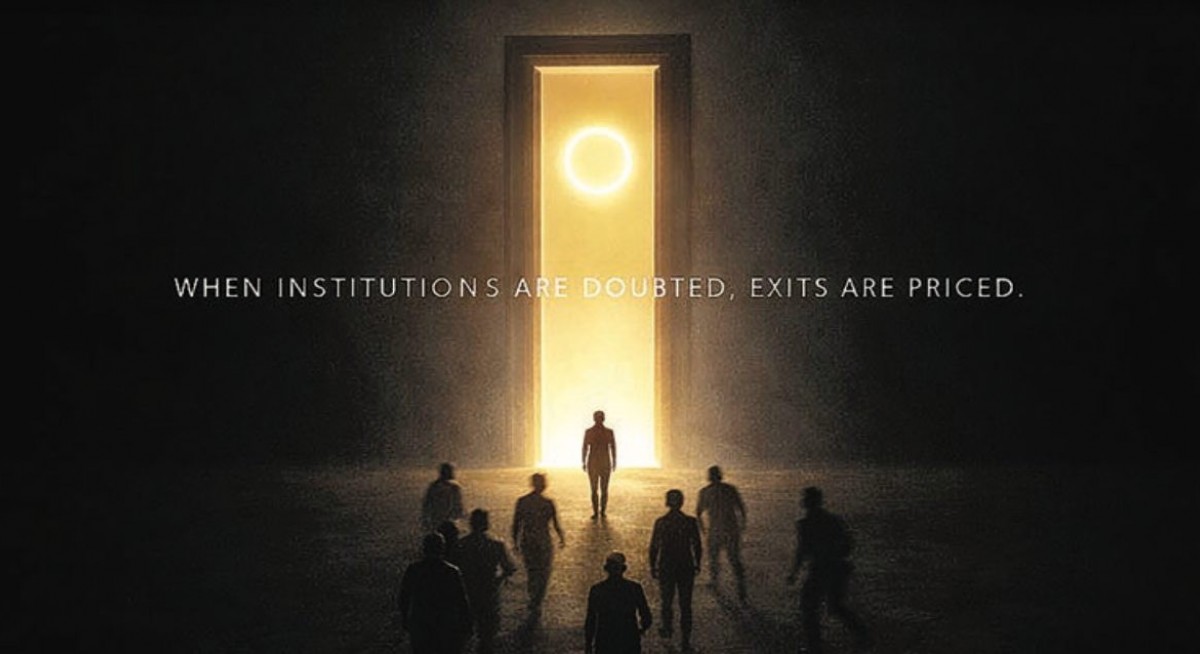

When trust in institutions weakens, capital does not wait for clarity. It exits. This pattern has repeated itself with remarkable consistency over the past 200 years. The capital flight is almost always into non-productive “exit assets” — stores of value perceived to be insulated from governments, banks or the prevailing monetary order. While the underlying motivations and outcomes remain the same, the form of these exit assets changes with prevailing technology and culture.

In the 19th century, distrust of paper money and sovereign debt drove wealth into land and gold. Agricultural land offered subsistence (food is non-optional), was tangible and protected against inflation, falling currency and urban instability. Gold offered portability and monetary neutrality, with a limited supply and no counterparty risk. During periods of crisis — such as wars, depressions or hyperinflations — these exit assets performed better than holding claims on the state (cash, bank deposits or bonds). But there was a cost to these exit assets. Land was illiquid and politically exposed. Gold generated no income (it has no yield), although it largely protected wealth.

Starting in the mid-20th century, those with wealth have faced a new set of risks. They needed to exit capital controls, confiscatory taxation (wealth tax, estate duties and global taxation) and geopolitical instability. The new generation of exit assets included Swiss banks, Caribbean structures as tax havens, and other secrecy jurisdictions. These investments (or instruments or structures) were not about returns to capital but about keeping wealth at a distance from domestic courts and regulators. These products — just like agricultural land and gold before — worked for several decades. But not anymore.

As states coordinated and transparency regimes emerged after 2008, regulatory arbitrage collapsed. Exit assets built on secrecy were neutralised once political will aligned. The same has applied to investment properties. Real estate works in inflationary environments: As rents adjust, leverage amplifies nominal gains and property is tangible. Yet, we have repeatedly seen how such exit logic can overwhelm into systemic risks, such as the property bubbles in Japan, the US and now China, Canada and many other countries.

Finally, rare but noteworthy as exit assets are the arts and antiques. They are portable, hard to confiscate and offer status and value preservation but require high net worth and expertise.

Crypto as an exit asset

For more stories about where money flows, click here for Capital Section

Against this backdrop, crypto assets can be said to be the latest reincarnation in this lineage — a modern digital exit asset. As such, crypto investing is not some brilliant new idea that mankind has just discovered. The product is driven by today’s technology and cultural embrace of digitalisation, but the motivation, reasons and outcomes are the same as before. This is the simple truth, without the evangelism: Once you strip away the bells and whistles — the technology from the product and the intellect from the narratives — what remains is fundamentally similar.

Like gold, cryptocurrencies promise insulation from fiat debasement; like offshore accounts, they offer mobility and autonomy from governments. The motivation is the same — only the medium is new. The consequences? It will rhyme with history. Cryptocurrencies are volatile in value, narrative-driven, non-productive and acutely sensitive to shifts in interest rates and regulation. They function as an escape valve, an exit asset, not a foundation for compounding wealth. Because of their huge price volatility, they may not even be a reliable refuge for wealth preservation. And so far, they have failed as a short-term inflation hedge.

Yet, despite these limitations, crypto investing remains highly attractive. Why?

The many functions of crypto

It is great for speculation with asymmetric payoff. A large upside with relatively small capital. A convex return where many may go to zero value, but a few will go up by 100 times or more. It is accessible to small retail investors priced out of properties and equities. Theoretically, it offers portfolio diversification since cryptocurrencies have low correlation with equities and behave like high-beta risk assets. For Bitcoin: Given its limited and fixed supply, there is some truth that it can serve as a hedge against fiat debasement, but its price is more volatile than inflation.

Cryptocurrencies also provide some measure of financial sovereignty in sanctioned economies, capital-controlled regimes and failed banking systems.

The democratising effect of cryptocurrencies is most visible in economies suffering from chronic inflation or impaired financial systems. Countries such as Venezuela, Turkey and Argentina have in recent years recorded sharp increases in cryptocurrency adoption during periods of monetary stress. In Venezuela, where hyperinflation “stabilised” at still-extraordinary levels of 400%-500% in the early 2020s, cryptocurrencies (most prominently Bitcoin and Dash) were widely transacted across peer-to-peer platforms, an instrumental lifeline for purchasing essential goods, receiving remittances and, where possible, storing value outside a collapsing monetary system.

The same logic has extended on a corporate level as well, with cryptocurrencies enabling transactions where conventional financial channels have become constrained. Russian oil exporters, facing Western sanctions, have reportedly increased their use of Bitcoin, Ether and stablecoins in oil trade with China and India. On the whole, traditional currencies continue to dominate the bulk of Russian oil transactions, but the growing use of cryptocurrencies nevertheless highlights their usefulness within environments where financial access has been monitored or weaponised.

Separately, cryptocurrencies are increasingly replacing gold for the younger generation. Gold offers security against mistrust of fiat money and weak institutions; it is portable across regimes.But is has no yield. Cryptocurrencies play the same role but without centuries of legitimacy. Cryptocurrencies also offer pseudonymity, self-custody and cross-border transfer — replacing benefits once offered by offshore Swiss banking, such as secrecy, mobility and regulatory distance. But where the Swiss banks only served the elites, cryptocurrencies can serve everyone. Hence, its popularity.

The cost of decentralisation

Of course, any balanced discussion about cryptocurrencies necessarily has to acknowledge its drawbacks. The very same properties that enable trustless transactions also make cryptocurrencies attractive for illicit activity. Because cryptocurrency transactions are decentralised, difficult to trace and irreversible in nature, this naturally makes them the preferred medium of the darknet, the unregulated underbelly of the internet where illegal commerce thrives.

A significant share of Bitcoin activity has been linked to illegal activity since its formative years: Between its inception and 2017, this was estimated to involve approximately one-quarter (26%) of users and almost half (46%) of transactions. Over time, the proportion of illicit transactions has declined as legitimate usage has grown, but the absolute volume nevertheless remains substantial. Blockchain analytics platform Chainanalysis crowned 2024 a record year for illegal cryptocurrency transactions, with an estimate of US$41 billion in turnover.

Beyond facilitating illicit exchange, the technical complexity and regulatory ambiguity of cryptocurrencies have also made it fertile ground for financial deception. The MBI Ponzi scheme, which operated out of Penang during the 2010s and defrauded millions of victims worldwide, is a case in point. Its proprietary token, the M-coin, was not a cryptocurrency in the strict sense, but borrowed crypto terminology and a digital branding to project a veneer of technological legitimacy.

This pattern is not new, either. Consider the collaterised debt obligations (CDOs) and other complex financial instruments that played a central role in triggering the global financial crisis — structured in ways too intricate for most investors to fully comprehend. Innovation, whether in technology or finance, frequently advances faster than the public can fully comprehend. After all, this is precisely what makes a breakthrough truly transformative. Unfortunately, this in turn creates gaps of understanding that are equally ripe for exploitation.

Conclusion: Cryptocurrencies in perspective

In conclusion, the true utility and value of cryptocurrencies are more complex than its advocates or critics suggest. Rather than resting on a single narrative, crypto’s value emerges from its underlying properties — digital, decentralised, disintermediated — and how these properties have in turn been adopted and repurposed over time. It is, as we are compelled to repeat, important to distinguish the speculative frenzy surrounding cryptocurrencies from the functional utility of its underlying technology, although both factors certainly contribute to their overall value and appeal.

One enduring function, which we have explored above, arises from the demand to hedge, protect and transfer wealth outside of mainstream financial channels. This partially explains why cryptocurrencies continue to hold value despite their inherently speculative nature and repeated predictions of demise.

But exit assets are defensive — accumulated when trust collapses, policy credibility erodes or inflation threatens contractual claims. They preserve optionality, not prosperity. While such behaviour is rational individually, it is corrosive collectively if it becomes widespread, depriving economies of investment. This leads inevitably to the state responding to close off exit routes — through reform, regulation and taxation.

The state reasserting control will come — history will repeat itself. Bitcoins and cryptocurrencies serve a purpose — like gold, offshore accounts and real estates in the past — as part of portfolio diversification and risk management, as a defence against society distrusts of governments and institutions, but they are not meant as an investment to build wealth. And if we were to learn from historical episodes, most people enter exit assets too late and leave them too slowly!

Portfolio performance

The Malaysian portfolio fell 1.8% for the week ended Jan 21, led by Insas Bhd - Warrants C (-62.5%), United Plantations (-9.6%) and Kim Loong Resources (-0.4%). The losses more than offset gains from LPI Capital (+1.2%), Hong Leong Industries (+0.8%) and Maybank (+0.5%). Last week’s losses pared total portfolio returns to 207.5% since inception. Nevertheless, this portfolio continues to outperform the benchmark FBM KLCI, which is down 6.8% over the same period, by a long, long way.

The Absolute Returns portfolio also ended lower last week, down 1.7% on the back of renewed uncertainties triggered by US President Donald Trump’s aggressive comments on Greenland. Against this backdrop, gold rallied. The SPDR Gold Minishares Trust was the biggest gainer last week, up 4.2%. Trip.com (-15.2%), ChinaAMC Hang Seng Biotech ETF (-5.4%) and Alibaba (-3.4%) were the top losers. Total portfolio returns since inception now stand at 45.3%.

The AI portfolio fell by 0.7%, reducing total portfolio returns since inception to 2.4%. The biggest gainers were Naura Technology (+3.5%), Marvell (+1.7%) and Horizon Robotics (+0.9%) while the top losing stocks were ServiceNow (-6.9%), Alibaba (-3.4%) and Amazon.com (-2.3%).

Disclaimer: This is a personal portfolio for information purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or solicitation or expression of views to influence readers to buy/sell stocks, including the particular stocks mentioned herein. It does not take into account an individual investor’s particular financial situation, investment objectives, investment horizon, risk profile and/or risk preference. Our shareholders, directors and employees may have positions in or may be materially interested in any of the stocks. We may also have or have had dealings with or may provide or have provided content services to the companies mentioned in the reports.