From his perspective, the reasons driving the industry’s growth is that demand for semiconductors has skyrocketed due to the advent of everything from cloud computing and machine learning to blockchain technology and artificial intelligence (AI) and the metaverse. These require a lot more computing power and semiconductors than before. “You have your gyrations for sure but that’s how most people and I look at it,” he adds.

Future demand

Should investors continue to plough money into semiconductor stocks then? Given the industry’s many moving parts, the answer is: It depends. Analysts say it is important to differentiate between the different kinds of chips out there in the market as well as the foundries that are manufacturing them. Not all chips are created equal and by extension, companies will be affected differently, they explain.

PhillipCapital’s Chua foresees that future demand for chips will be driven by “high-performance computing” used to power AI capabilities, a segment that has seen revenue grow to 23% in 2021 over 2020, outpacing applications like the Internet of Things and smartphones.

Analysts say market leaders TSMC and Samsung Electronics will stay ahead of the competition, especially at the higher-end segment of the market, where 7nm (nanometre) chips and more advanced 5nm chips are produced.

TSMC, in particular, has a clear lead given the company’s strong earnings can fund greater capacity, which, in turn, leads to even stronger earnings. This creates a virtuous cycle that keeps it ahead of everyone else. Morningstar’s Lee estimates that TSMC should be able to maintain its market lead in cutting-edge chip technology and its more than 50% market share in the foundry market in terms of revenue.

See also: Nvidia-led boom set to turn chips into trillion-dollar industry

Rather than trying to spend heavily and compete head-to-head, smaller foundries tend to expand by focusing on chips that are technologically more mature or older. As Ling of DBS points out, there will still be demand for lower-end chips similar to those found in basic consumer electronic products. As such, she expects demand to be “quite well spread”. Temasek’s Tham agrees that while the focus is on the most advanced chips, demand is “going gangbusters” or skyrocketing for many high-growth end-products such as electric vehicles (EVs) that can make do with older chips which are cheaper. Then there are the companies upstream and downstream of the foundries. Those upstream are companies that make the machines that enable TSMC and Samsung to produce their chips. The big name in this space is Dutch company ASML, which was spun out of technology giant Philips in 1984. ASML claims it has between 80% and 85% share of the total market for lithography systems that make semiconductors and when it comes to the most advanced type of chipmaking lithography machine known as extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV), its market share surges to 100%. Each machine costs some US$150 million — slightly more expensive than the cost of a US F-35 fighter jet. ASML supplies these EUV machines to customers like TSMC and Intel, allowing them to produce cutting-edge chips which are used in devices that require high processing power such as data centres, VR and AR devices, and supercomputers. The company’s dominance in this area is currently unchallenged, with ASML claiming that its most advanced technology is so complex that it would take at least 15 years for others to replicate. It was so critical to the semiconductor supply chain that at the end of 2021, ASML was named Europe’s largest public tech company by market cap, boosted by demand for devices and the global chip shortage during the global pandemic. However, ASML’s position in the supply chain means that any developments affecting the company will have knock-on effects on chipmakers downstream. On March 21, the Financial Times quoted ASML CEO Peter Wennink as saying the multibillion-dollar expansion plans of chipmakers will be constrained by a shortage of critical equipment over the next two years as the supply chain struggles to step up production. Wennink reveals that there will be shortages of lithography systems in 2022 and 2023, adding that although the company will ship more machines, “it will not be enough if we look at the demand curve. We really need to step up our capacity significantly more than 50%. That will take time”. He also adds that ASML was working with its suppliers to assess how to increase capacity. While it was not clear what scale of investment was required, Wennick says ASML has 700 product-related suppliers, of which 200 are critical. As at April 8, ASML’s share price stood at EUR569.3, almost double compared to 2020. On the other hand, there are the customers of the foundries: the so-called “fabless” companies. These include the likes of AMD, Nvidia and Qualcomm. Broadly speaking, they design and sell their hardware devices and semiconductor chips but outsource their fabrication to a foundry. Then there are the companies that try to do both, like Intel. Called IDMs or integrated design manufacturers, they design and manufacture their chips completely in-house.

Singapore opportunities

Once upon a time, Singapore had its very own foundry in the form of Chartered Semiconductor Manufacturing. While the facilities are still physically here, the company is now part of what is known as GlobalFoundries, a Nasdaq-listed entity backed by the United Arab Emirates government.

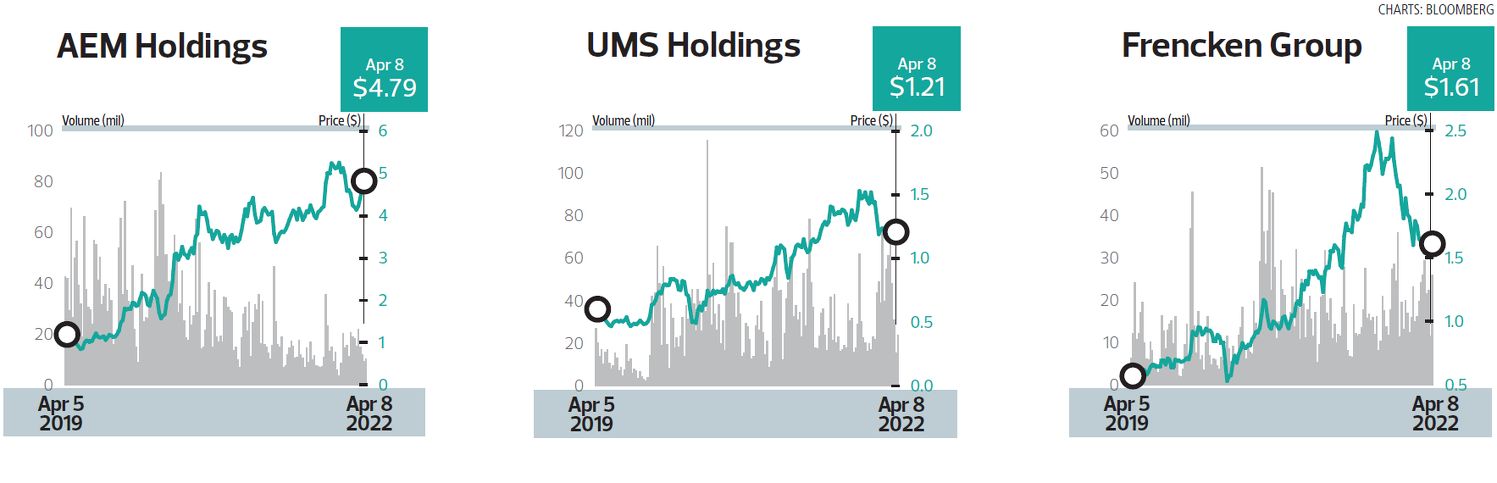

However, the Singapore Exchange has a list of companies that are tied to the industry, whether directly or indirectly. Names like AEM Holdings and UMS Holdings service major customers like Intel and Applied Materials respectively, while Frencken Group counts ASML as one of its customers as well as Philips Healthcare and GE Healthcare.

While their respective financial performance will vary according to competitive strength, product positioning and the customers they have, Ling of DBS thinks that “generally for those stocks, we still expect the uptrend to continue”.

However, Ling says UMS’s growth rate probably will not be as strong as it was in 2021, partly due to a higher base effect. She adds that AEM’s earnings growth was weaker in 2021 due to a product transition but 2022 should see a strong recovery due to the mass production of the new product.

On Jan 11, AEM had raised its FY2022 ending December revenue guidance to between $670 million and $720 million. However, it expects some margin compression “in view of higher supply chain costs and an increase in R&D spend as we engage customers on new projects”.

AEM reported FY2021 ended December 2021 with revenue of $565 million, 9% higher y-o-y, with 2HFY2021 revenue and profit before tax described as the highest in the company’s history. 2HFY2021 revenue stood at $373.2 million, 52.2% higher y-o-y, with profit before tax coming in at $75.6 million, representing a 62% y-o-y increase.

Meanwhile, UMS reported that the acceleration of global chip demand has “propelled it to another record-breaking performance for the nine months ended Sept 30, 2021”.

This boosted its FY2021 earnings ended December 2021 when it reported a 59% increase to $57.6 million while revenue came in at $271.2 million, an increase of 65% compared to the $164.4 million in FY2020.

In the release on Feb 28, UMS says the “exceptional performance” was driven by a sustained acceleration of global chip demand as well as the increasing capex of semiconductor fabs worldwide.

UMS says this is also its highest-ever annual revenue, surpassing $250 million for the very first time. As a result, the company will be doubling its proposed dividend from one cent — announced in FY2020 — to two cents in FY2021.

Earlier in its 3QFY2021 report, UMS says it expects to increase its production capacity by doubling its capex in FY2022 to take advantage of this ongoing global semiconductor boom, saying its new Penang factory is scheduled for completion in 3QFY2022.

As for Frencken Group, the company recorded a smaller increase of 23.6% in revenue for FY2021 ended December 2021 to $767 million and a 37.3% increase in earnings to $59.1 million.

In the release of its results, Frencken said this was driven by strong demand from customers in the semiconductor, analytical & life sciences and medical segments. The company notes that while the automotive segment improved year-on-year in FY2021, customer demand was constrained by the semiconductor chip supply challenges.

Frencken says to meet the overall demand from customers, it has been ramping up its output capability and increasing production space with new facilities in Europe, Malaysia and Singapore. Barring any unforeseen circumstances, the company expects a moderate increase in its revenue in 1HFY2022, compared to 2HFY2021.

However, even with these figures, year to date, AEM, UMS and Frencken’s share prices have lost 8.94%, 20.94% and 18.27% respectively as of April 8.

Despite the dip in local stocks, it should be safe to say that the demand for semiconductors will continue and despite analysts being uncertain on when the impending surge in supply and normalisation of prices will happen, investors in semiconductor companies, such as market leader TSMC, will find themselves in a good position as the world continues to demand more of these valuable bits of silicon.

Or as Dune puts it, “the spice must flow”.

See also: TikTok hit by EU ultimatum over addictive design dangers

Or as Dune puts it, “the spice must flow”.