Why aren’t more investors shifting their strategies? First, net-zero alliances and climate frameworks such as the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance have historically focused on reducing financed emissions, sometimes setting very rigorous and steady decarbonisation pathways to follow. However, tilting portfolios away from carbon-intensive assets and towards companies that are net-zero aligned results in so-called paper decarbonisation.

See also: A rejuvenated Singapore market, a reset for The Edge Singapore

See also: From momentum to transformation: Building a relevant stock market

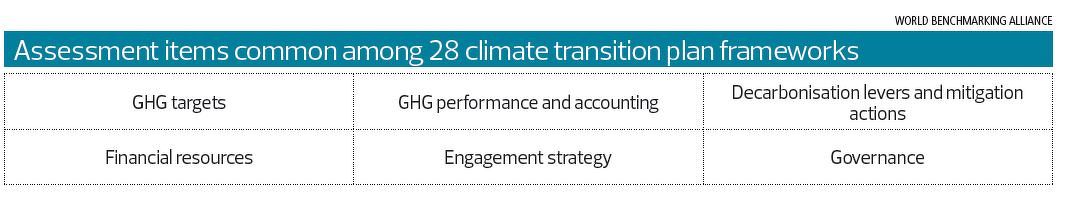

How investors can act now Morningstar Sustainalytics’ Low Carbon Transition Ratings (LCTR) provide 85 risk management indicators, which are aligned with the aforementioned frameworks, and can be used to accommodate investor preferences and serve a variety of needs. These needs can be classified into four broad categories: Meeting the demands of a given framework or label: In this case, investors need to ensure alignment with a specific framework they have committed to, such as the French SRI label or the NZIF 2.0. A growing number of asset managers are actually setting targets based on NZIF portfolio alignment, and could use, to that end, the NZIF solution developed by Morningstar Sustainalytics. Feeding a proprietary ESG tool: Investors may want to enhance their own in-house ESG tool by incorporating data that addresses issuers’ ability to decarbonise over the long term and manage climate-related transition risks. An example of this is Lombard Odier’s sustainable investment framework, which assesses, among other things, the existence of a “clearly articulated and ambitious transition strategy to sustainable activities”. Creating a proprietary and dedicated climate transition assessment: Some investors have developed or need to build in-house tools focused on the assessment of issuers’ climate transition readiness. For instance, Spanish bank BBVA has developed a transition risk indicator that assesses exposure to transition risks, ambition, and credibility of transition plans, while Dutch Bank ING is using its own “client transition plan” score. Informing specific activities, such as banking advisory, research, and stewardship: These activities require granular data to identify on which specific items a discussion could be held. Alliance Bernstein, for instance, has developed a new framework that broadens the scope of risk called ESD, which stands for “Emerging, Strategic, and Disruptive”. In the automotive industry, those risks include, among others, carbon pricing mechanisms. Conclusion The need to carry out forward-looking assessments of climate transition plans, moving beyond analysing commitments, is undeniable. It makes economic sense for investors, is recommended by international organisations and standards, and is making its way into regulation and supervision. By leveraging transition risk and management data, such as Sustainalytics’ Low Carbon Transition Ratings, investors can build and use a proprietary assessment tool that is aligned with leading climate transition frameworks and labels, while retaining enough flexibility to accommodate the specificities of each investor. Adrien Poisson is senior associate, client relations, client advisory at Morningstar Sustainalytics